At the beginning of the last century, smoky air and sewage-filled water plagued Chicago. So when a group of civic-minded residents wrote the 1917 Plan of Evanston, they focused on trees and parks, calling them “in sober, literal truth, the lungs of a city.”

Now, just over a hundred years later, the City Council is poised to adopt an ordinance that will strengthen protection of trees on private property. With more than 70% of Evanston’s urban forest located on privately owned land, it’s a move of vital interest to the whole community and a goal of the 2018 Climate Action and Resilience Plan (CARP).

“A community resource that benefits everyone”

Evanston’s early planners may have been aware of the connection between burning of fossil fuels and the possibility of climate change on a global scale. Scientists had been writing about the phenomenon since the 1850s at least. But the connection between climate-heating carbon emissions and city trees has become clear only in recent years.

Since the concept of the “urban forest” came into use in the 1970s, thousands of studies have established exactly how city trees protect public health, not only directly but over the long term, by mitigating and helping us adapt to climate change.

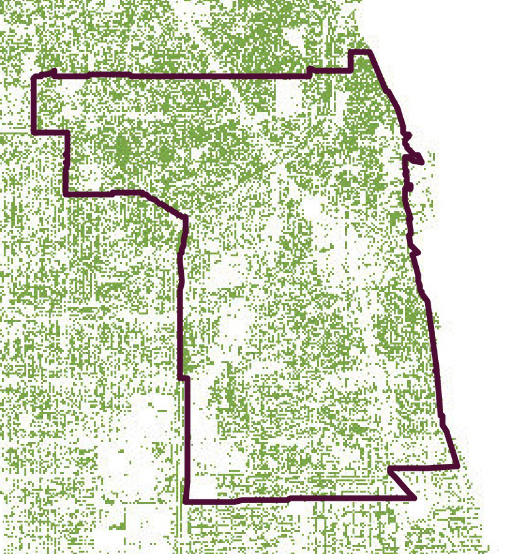

Using tools based on this research, the Chicago Region Trees Initiative has estimated that just three of the climate-related services provided by Evanston’s urban forest – reduced stormwater runoff, carbon sequestration and improved air quality – provide $2,089,000 worth of benefits every year. In addition, carbon stored by Evanston’s trees is valued at $3,614,000. Trees also mitigate the urban heat island effect, reducing temperatures on average 2.9°F over areas without trees, one reason the EPLAN targets increased tree canopy cover as a priority for neighborhoods in western parts of Evanston where coverage is lowest. That is in addition to myriad other tangible benefits of city trees, including improved mental health.

Satellite images showing Evanston tree canopy (left) and surface temperature (right) in September 2014. Credit: Chicago Region Trees Initiative

Areas with lower tree canopy, concentrated in western parts of Evanston, are hotter. These coincide with neighborhoods that were historically redlined. Credit: Chicago Region Trees Initiative

Areas with lower tree canopy, concentrated in western parts of Evanston, are hotter. These coincide with neighborhoods that were historically redlined. Credit: Chicago Region Trees Initiative

As Cherie LeBlanc Fisher, urban forestry expert and former co-chair of the Environment Board, has said, “it is easy to think of trees on private property as privately owned, but they are a community resource that benefits everyone.” Which of us hasn’t sought out a parking place or crossed to a sidewalk shaded by trees?

“It is entirely within the province of the City to supervise a man’s trees”

Even without knowing all we do now, early planners believed that the community as a whole had an interest in protecting all trees. In the 1917 Plan of Evanston, they recommended (in gendered language of the time) that “Nobody should be permitted to cut down a tree in his parkway, or in his own yard for that matter, without a permit from the City Tree Warden.”

“You may say to yourself,” they wrote, “that the City has no right to supervise the trees on a man’s property; he can do what he likes with his own. This we think is not right. If one man wantonly destroys the trees on his ground, he is doing an injury to his neighbor and to the entire community. We feel that it is entirely within the province of the City to supervise a man’s trees just as much as it is to look after the health of the same man’s neighbors by making him comply with the City sanitary requirements.”

What about the trees in your yard?

Trees located on private property make up about 70% of Evanston’s urban forest. Not all of these trees will be subject to the new ordinance. Those less than 6” in diameter at breast height (DBH) are exempt. Bigger trees that are “dead, extremely hazardous, imminently dying” or invasive (like tree of heaven) will require only a simple permit, which will help the City keep track of removals and encourage property owners to plant new and healthier trees. Also, trees that provide fewer ecological services (a box elder compared to an oak, for example) will have lower requirements for mitigating their removal.

Libby Hill, steward of Perkins Woods, measuring an old oak tree using a tape measure that converts circumference to diameter. Credit: Wendy Pollock

Libby Hill, steward of Perkins Woods, measuring an old oak tree using a tape measure that converts circumference to diameter. Credit: Wendy Pollock

The main aim of the ordinance is to preserve trees that are already well established and likely to provide important ecological services for many years to come. Preserving trees this size is important because big trees provide much greater benefits than small ones.

You can estimate the ecological services provided by your own trees using iTree, a US Forest Service calculator based on extensive and ongoing research. About 12 years ago, for example, we planted a swamp white oak behind our house. It now measures about 5” DBH, so it’s not yet covered by the ordinance. According to iTree, the tree sequesters 12 pounds of carbon and intercepts 279 gallons of stormwater annually and is now storing in its wood about 133 pounds of carbon. If this tree keeps growing to 15” DBH (which will take about 80 more years), all of the ecosystem services it provides every year will have greatly increased, and the tree will have stored an estimated 1,155 pounds of carbon.

All the carbon we can keep out of the atmosphere makes a contribution to mitigating climate change. As the tree grows taller, provides more shade and blocks wintry winds, it will also help to reduce use of energy for heating and cooling. And as storms grow more extreme, it will continue to intercept and absorb stormwater and reduce the strain on the city’s stormwater sewer system.

We won’t be here to reap all of those benefits, but we knew when we planted the tree we were planting for the future, and we are glad to do our bit to grow and conserve Evanston’s urban forest.

Now that the City Council has committed itself (in the 2022 Declaration of a Climate Emergency) to implementing the climate action plan, one of the century-old recommendations to protect the urban forest may finally be realized.

You can read the proposed ordinance here, starting on Page 373. A separate policy document will provide details, and if the ordinance is adopted, the staff will carry out a public education campaign over coming months. The vote is scheduled for Sept. 11.

evanstonroundtable.com

https://evanstonroundtable.com/2023/09/10/protecting-trees-has-deep-roots-in-evanston-history/