Everyone I talk to about Thomas Solinsky has a different nickname for him. To some he is “Nashville’s Johnny Appleseed” and to others “The Ultimate Connector”. Or as the country singer and “friend of Thomas” Dierks Bentley puts it: He is “The Tree Ninja”.

Solinsky estimates that he has planted more than 40,000 trees in Tennessee and surrounding states over the past 15 years. He’s planted them in woods, along waterways, and even in elephant and pig sanctuaries, but is most proud of the “urban forest” he cultivates throughout Nashville — on sidewalks, on medians, and in front of businesses and homes.

“He puts up these trees without people even realizing, and years later they’re looking around the neighborhood and they’re like, ‘Gosh, this is all the work of one person,'” says Bentley, who met Solinsky. after accidentally meeting him while planting a tree was out for a walk.

In cities like Nashville, where new construction is increasing, trees counteract the urban heat island phenomenon – the temperature-raising effect of natural green spaces being replaced by heat-retaining buildings and asphalt roads. Trees help with stormwater management and absorb greenhouse gases emitted from the atmosphere. Studies also suggest that urban trees improve the mental health of surrounding residents.

“Actually, I don’t like to talk about the number of trees planted, but about the impact,” says Solinsky. “Where trees have been felled in cities, they cannot shed their seeds naturally and cannot regenerate. A single tree has so much benefit when planted in an urban area.”

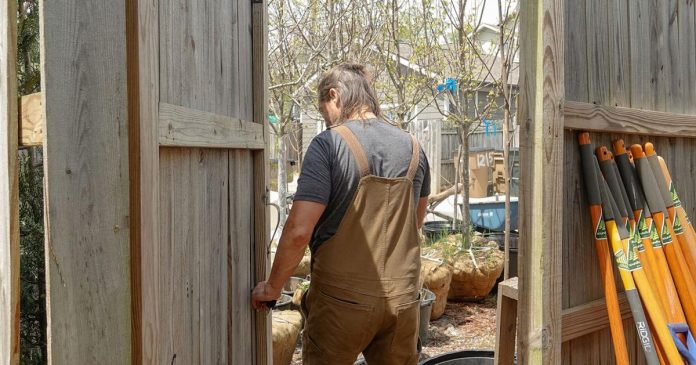

Trees planted by SoundForest outside of the Frothy Monkey at 12South

Solinsky conceived his project, officially known as SoundForest, in 2008 — at a time when he says almost nobody in Nashville was actively planting in urban areas. Though he began his work in partnership with local and state governments, Solinsky deplores the “bureaucracy” of planting trees through official channels.

People wishing to plant on Nashville’s public right of way must obtain Metro Nashville’s approval, and Solinsky recalls there was a “huge backlog.”

“I had a huge area that I wanted to cover and I didn’t get an answer,” he says. “The wait time to get people [from Metro] It took me so long to get out. I was like, ‘I’m done. I’ve got to go and have these trees planted on my own.’”

Solinsky says he hasn’t had any negative feedback from the city since he started planting on his own terms around 2015, but stresses that he follows the city’s street tree safety regulations closely.

Solinsky relies on donations and the volunteer labor of family, friends and neighbors—from employees at local businesses to students at the University School of Nashville. Frothy Monkey owner Ryan Pruitt recalls how Solinsky suggested planting trees in front of the cafe’s front porch and hosted a SoundForest fundraiser at the cafe.

“It’s rare that Tom has a crazy idea and then doesn’t do anything with it,” says Pruitt.

As part of his SmartYards initiative, Solinsky is planting trees that shade and cool air conditioners in residential buildings. This strategy can increase the efficiency of residential units by up to 25 percent. The program focuses on Nashville’s most economically vulnerable city blocks, which are also those with the fewest trees and the greatest associated negative health impacts.

In 2018, the city invested $2.5 million in its first coordinated urban tree-planting campaign, Root Nashville. Campaign manager Meg Morgan says the project built its reach on grassroots initiatives like SoundForest.

“I commend anyone like Thomas for doing this work alone,” says Morgan. “Thomas plants trees in areas where he lives, where he has really deep connections.”

Despite the best efforts of environmentalists, the city’s most recent survey found that Nashville’s tree canopy shrank by more than 13 percent from 2008 to 2016. Canopy conservation regulations remain sparse for developers, and legislation that would tighten tree protection standards was withdrawn in February. Metro Water Services sustainability coordinator Rebecca Dohn reckons that even Root Nashville’s goal of planting 500,000 trees by 2050 may not reverse canopy loss.

Solinsky says he keeps his drive going by focusing on planting and tending trees not just as a public service or political strategy, but as an ongoing practice.

“Planting trees is my exercise — it’s therapeutic,” says Solinsky. “It’s more than just, ‘We’re planting trees for this purpose.’ It’s a way of life.”

When I ask Solinsky about the favorite tree he’s planted, he describes the tree under which he buried his beloved dog, Rowan. Solinksy dedicated trees to his children and in honor of a parishioner after his death.

“There’s a saying that the best time to plant a tree was 25 years ago and the next best time is now,” Solinsky said when asked what he’s most looking forward to about the future of SoundForest. “25 years from now I’m going to look back at the trees I plant today and be like, ‘Dude, it’s so cool to see they’ve grown so big.'”

www.nashvillescene.com

https://www.nashvillescene.com/news/citylimits/tree-ninja-cultivates-a-forest-in-nashville-s-neighborhoods/article_737ae7fc-fefd-11ed-a0ec-07bb4b1cdc5f.html